|

Who’s the Forger?

At least one question about the fake

Leonardo bicycle remains, namely “who done

it?” Although Marinoni has been overly

gullible, rejecting all reasonable arguments

about the drawing being a fake, it should by

no means be suggested it is he who drew the

lines that made the circular outlines

showing through from an unrelated drawing on

the front into a bicycle on the back. Nor

has anyone so far pointed a finger at the

monks of Grottaferrata.

Unfortunately, some writers (including

Jonathan Knight of the New Scienctist

and Frederico di Trocchio in L'Espresso)

have interpreted the information that way,

and thus indirectly implicated Prof. Lessing,

the author of our article, as being the

source of such speculation. The reader is

invited to judge for him- or herself whether

Prof. Lessing is making such claims in the

following texts.

|

Until some time ago, if you

Click here you would get a link to the related web site for the

original article by Prof. Federico di Trocchio in the

Italian weekly L’Espresso.

Update: Unfortunately, this link is no

longer active |

|

The Evidence against “Leonardo’s Bicycle”

Text of a paper presented at the 8th

International Conference on Cycling History,

Glasgow School of Art, August 1997

Prof. Dr. Hans-Erhard Lessing

News of a bicycle-like sketch said to

have been discovered during the ten-year

restoring period of Leonardo da Vinci’s

Codex Atlanticus popped up in 1974, when

literary historian Augusto Marinoni gave a

lecture in Vinci, Leonardo’s birthplace.

From the chronology of disclosures and (in

part circumstantial) evidence, it is now

becoming clear that we are dealing with a

recent forgery.

|

|

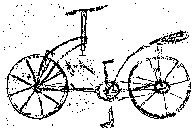

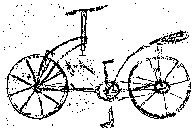

Several nations have been involved in the

bicycle’s (and the motorcycle’s) development,

and some decisive concepts can be attributed to

individuals within those countries. Thus, for

example, the basic two-wheeler concept on which

all bicycles are based is attributed to Karl von

Drais, a civil servant with a background in

technology acquired at the University of

Heidelberg in Germany.[1

(Footnotes can be accessed by clicking the

appropriate line "Click here for

footnotes/bibliography" above or the individual

footnote number in the text)] Drais’ invention

is well-documented with patent specifications

and other materials which suggest that it was

unprecedented.

Nevertheless, the competition between the

industrial nations leading to World War I

created jingoistic priority myths, usually

launched to attribute priority to the forger’s

nation. Even before this conference was

initiated in 1990 by Nicholas Clayton to replace

such myths by serious historiography, our French

delegate Jacques Seray had been able in 1976 to

destroy the non-steerable two-wheeler myth

created in France in the 1890s and generally

accepted thereafter.[2]

But until 1976 it was believed worldwide that

the first incarnation of the two-wheeler

principle was not steerable (a myth that is

still repeated by some today), and therefore

competing priority myths depict unsteerable

two-wheelers, too.[3]

Seen in the light of Seray’s research,

“Leonardo’s bicycle” publicized worldwide in

1974[4]—and

again non-steerable—left bicycle historians like

Derek Roberts skeptical, since a “law of series”

appeared to apply.[5]

Evidence:

The “Leonardo bicycle” sketch shows a non-steerable

two-wheeler in an attempt to outdo the false

French priority which was still believed to be

correct before 1976.

This is also confirmed by a comparison of

the pictorial bicycle evolution taken from the

standard Italian book on history of technology[6]

and from Marinoni, Ref. 19 (see Fig. 2).

The Sisyphean task of tracing the debate on the

restoration of Leonardo’s Codex Atlanticus

in Italy thirty years ago is eased by the fact

that Augusto Marinoni, an Italian lexicographer

and philologian, then at the Catholic University

of Milan, appears to be the only maintainer of

the genuineness of the bicycle sketch among

Leonardo scholars. Catalogues of exhibitions and

books where Marinoni was not involved

demonstrate a conspicuous absense of the bicycle

sketch (e.g., Ref. 12). In what follows, I will

concentrate on the bicycle sketch alone.

The restoration of the Codex Atlanticus

was the result of an initiative of engineer

Nando di Toni,[7]

who ran a Centro Ricerche Leonardiane in Brescia

with a newsletter Notiziario Vinciano,

and French Leonardo scholar André Corbeau, who

managed to exhibit original sheets from the

Codex in Paris as early as 1961. This may

account for the different durations given for

the restoration period: While Marinoni talks of

ten years, between 1960 and 1970 (presumably to

include dismantling of the album for the Paris

exhibition), the director of the Biblioteca

Ambrosiana in Milan specified the restoration

period as 1966 until 1969.[8]

Pope Paul VI, born a Brescian and at that time

archbishop of Milan, gave his consent to the

restoration under the condition that it was to

be performed by monks in the cloister

Grottaferrata near Rome for the reason that the

Codex Atlanticus and the Ambrosian

Library belong to the Vatican.

An American in Madrid

Nine monks had already been working on the

restoration of the Codex Atlanticus for

one year at Grottaferrata when sensational news

electrified the press worldwide in 1967: Jules

Piccus, a Bostonian Romanist, had accidentally

discovered two albums of Leonardo notes and

drawings in the National Library of Madrid when

ordering something else. These were called

Codices Madrid henceforth. The news[9]

was accompanied by a sample page (Fig.3),

definitely showing chainwheels with chains for

lifting buckets with counterweights for wells or

the like, the idea being apparently to replace a

rope and pulley in order to prevent the rope

from jumping off the pulley or to avoid early

attrition. Leonardo’s handwriting there says,

“How to make the rope of a counterweight, which

never winds upon itself, pull with strength…”

Reti was enthusiastic:[10]

“... Leonardo’s beautiful sketches of a

hinged-link chain for a wheel-lock of a gun[11]

were well known, but that chain had only a few

links and, of course, was not endless. Now we

have a whole collection of true chain-drives and

sprocket wheels. In case we should be in any

further doubt, attention is called to the little

drawing at the bottom, where a complete assembly

is masterfully sketched.”

Thirty years later this has given way to a more

sober interpretation:[12]

“…Leonardo designed several types of chains. He

especially recommended their use in preference

to ropes for lifting heavy loads. He did not,

however, seem interested in exploring the use of

chains to transmit motion.”

But at their press conference in Boston on

February 1967, apparently Piccus or Reti had

popularized the transmission chain as

“bicycle-like.”

Evidence:

The worldwide communication of the

popularisation “bicycle-like” for the

transmission chains from Codices Madrid

suggested the forgery of a “Leonardo chain

bicycle” to the forger(s), allowing the forgery

to be dated to the post-1967 period. An

identical chain drive appears in the bicycle

sketch put into the Codex Atlanticus.

It seems that the library’s director in

Madrid became disenchanted with this press

interpretation and cancelled his contract with

Piccus and Reti, contacting scholars in Milan

and London for the facsimile edition of the

Codices Madrid.[13]

A Bicycle Like New

Let us turn to the debate after Marinoni had

released the bicycle sketch in a lecture[14]

at Leonardo’s birthplace Vinci on April 15, 1974

covering the Codices Madrid—although the

bicycle sketch was found in the Codex

Atlanticus. At the time of this lecture, the

printing of the bicycle sketch was irrevocably

underway in the Italian original of The

Unknown Leonardo (Ref. 4) and in volume Two

of the new Giunti facsimile,[15]

which may have been one reason for the delayed

disclosure. Or is there another reason to

withhold disclosure of a seemingly sensational

discovery for four years or more?

Marinoni never gave the details, nor the date of

his discovery. In his presentation, he tried to

disprove the objection from an undisclosed

source that a youngster may have manipulated the

sketch into the Codex around the turn of the

century— presumably a rhetorical position he

thought up himself. It is, of course, not good

academic style to conceal names or quotes of

opponents—and Marinoni holds back the fact that

the Codex Atlanticus had undergone a

ten-year reproduction for the old Hoepli

facsimile[16]

at the turn of the century, providing access to

it for many. Also it is the experience of this

conference that jingoism befalls those with

greying temples rather than young people.

The bicycle sketch became known worldwide

through the popular three-volume set The

Unknown Leonardo in 1974. Not many then

realised that the bicycle find was not in volume

3, Leonardo The Inventor, where it would

have belonged, but banished into an appendix to

the second volume, Leonardo The Scientist,

among whose authors was Augusto Marinoni—an

indication of a dissension between sceptic

editor Reti and maintainer Marinoni. Clearly the

sketch is not from Leonardo’s hand, and without

proven contemporaneity of the scribbles,

Marinoni’s tale of a pupil copying the bicycle

from a lost drawing of his master remains mere

speculation.

After Marinoni had placed the news[17]

in the Italian weekly magazine L’Espresso

under the title “A Bicycle like new,” several

authors came to the rescue of Italian

scholarship. Nando de Toni, former member of the

Commissione Vinciana, wrote the following letter

to the editor:[18]

“As to the bicycle, I want to indicate that on

various occasions some sheets from the Codex

Atlanticus have left more or less officially

the Ambrosiana before the restoration requested

by friend André Corbeau and the writer. Whoever

had the opportunity to take away, bring to

Florence, or send back from Lugano by mail,

sheets of Leonardo, robbed from the Ambrosiana,

was very well able at different times to poke

fun at the descendants by drawing that

rudimentary bicycle. To pretend to be a result

of the times of Leonardo it certainly did not

need to have the fenders, the chain cover, the

brakes, the headlight, the bell and the rear

reflector. It was sufficient to leave the idea

of pedals, of multiplication, of chain

transmission, of the seat, and of the

handlebars, even when it is obviously not

working in the end.”

One has to add that Marinoni always works with

the model of a naive forger who longed to put in

a modern steel bike, only prevented from doing

that by his own ineptitude. Marinoni’s reaction

can be read in his brochure on Leonardo’s

automobile and bicycle[19]—

he disproves statements that de Toni never made:

“Sticking to the idea of a forgery, the engineer

Nando de Toni proposed in a letter to

L’Espresso, that had published a short note

by the author in April 1974, the following

solution to the “who-dunit.” As is known, during

a series of thefts in the Ambrosiana in the year

1966, also a sheet of the Codex Atlanticus

was lost. According to de Toni, this should have

concerned sheet No. 133. To raise the value of

his prey, the thief should have sketched a

bicycle on it, believing that one would regard

any scribble, however senseless, as the work of

the universal genius and forsighted Leonardo da

Vinci. What a foolish thief had indeed expected

to be able to imitate Leonardo this simply? In

reality, the drawings concerned were on sheets

342–43 according to the old count, and have been

published in the weekly magazine Epoca of

November 24, 1963. Other sheets never left the

Ambrosiana, and sheet 133 was at the time of the

theft already in Grottaferrata for restoration,

since the Codex was brought there in parts.”

The strategy is to give the reader the

impression that the opponent has been disproved

completely without letting him know the

opponent’s argument.

Another member of the Commissione Vinciana, Anna

Maria Brizio, art historian at the university of

Milan and coauthor of The Unknown Leoardo,

was interviewed[20]

by the monthly magazine Panorama:

“The point is to ascertain if the sketch of the

bicycle was already on the back side of sheet

133, when Pompeo Leoni assembled the manuscript

at the end of 1500s, or if somebody put it in

during a following epoch. How can one be sure

that in 300 years of migration the sheet had not

fallen in the hands of an extemporaneous

draftsman? To solve the question, it remains

only to consult the experts: only a chemical

test could tell if Leonardo’s bicycle is another

marvelous anticipation or a vulgar scrawl.”

Marinoni replies like this:

“…Professor Anna Maria Brizio, who uttered

skepticism for the case, based her opinion on

the following arguments: Firstly, we are not

certain that the sheet has not fallen into the

hands of a hobby drawer during its 300-year

migration. Secondly, the bicycle was drawn with

a different ink than Leonardo used for the

fortification on the front side of sheet 133.

The first argument was already partly

invalidated by the journalist who didn’t

consider the error of the 300-year migration in

detail (it presumably never happened in reality)

but who remarked correctly that the first modern

bicycle goes back to the year 1885 and that

therefore the “forgery”—if one has to do with

that—could not have originated before the end of

the last century. But the journalist did not

know that the sheet was in the codex in 1965 and

that the forger could have been only one of the

restorers or the first scholars concerned with

the project (possibly even the undersigned). The

second argument, however, is an improvised wrong

assumption, since we have not an ink drawing—as

already said—but a pencil drawing.”

Apparently a chemical analysis or an age test

was never performed on the bicycle sketch. And

like in the famous case of the Piltdown Man, we

always have the option that Marinoni was the

uninitiated discoverer of what was done by a

different forger or forgers. However, an

important piece of evidence in dating the

bicycle sketch is that it is not from Leonardo’s

hand and produced no visible set-off overleaf in

contrast to the obscene scribbles surrounding

it—an indication that it has been put in after

the unfolding of the sheet.

An International Opponent

A serious blow to “Leonardo’s bicycle”

appeared in Carlo Pedretti’s catalog of the

restored sheets of the Codex Atlanticus.[21]

The art historian at the University of

California, Los Angeles (UCLA) describes the

restoration as chaotic—he always talks of the

monks as “restorers” in quote— and gives

examples of how they made things worse. He

deplores the lack of any scientific report by

the “restorers”—reportedly some sketches have

disappeared through the use of unknown

chemicals. About the obscene back side of sheet

132 he writes:

“Scribbles, not by Leonardo, probably not from

Leonardo’s time. Self explanatory.”

And on the back side of sheet 133:

“Scribbles, including the word “salaj,” not by

Leonardo, probably not from Leonardo’s time.

Self-explanatory. See f. 132 verso, to which

this sheet was originally joined. When I

examined the original sheets in 1961, holding

them against a strong light so as to detect

elements of their (at the time) hidden versos, I

noticed the presence of scribbles in black chalk

as well as light traces of circles in pen and

ink, which appeared to be the beginning of some

geometrical diagrams. These have turned out to

be part of a rough sketch of a vehicle that

resembles a bicycle. Similar rough sketches, not

by Leonardo, are found on other sheets of

Leonardo’s manuscripts and drawings.”

And he encloses a sketch from memory[22]

of what he saw in translucence back in 1961

(Fig. 3 top); in a postscript he attributes no

significance to the bicycle scribble:

“The scurrilous scribble of a pupil on the verso

of a two-part sheet of fortification studies,

ff. 132 and 133, hardly deserve the attention

they have received in recent publications, and

even less so does the sketch of a bicycle.”

He quotes Marinoni by Ref. 4 and Ref.

14.Marinoni replies to Pedretti in his

brochure, again disproving statements that were

not made:“Apparently Pedretti is convinced that

we have to accept his unfounded judgement simply

quia ipse dixit. Still he acknowledges that the

drawings are authored by a young man, a pupil,

but whose pupil?? Certainly not Leonardo’s, if

we assume following Pedretti that Leonardo had

been dead a fairly long time. How could a young

man—some tens of years later—have remembered

another young man having lived much earlier and

infuriated without reason against the shadow of

a past meanwhile long gone? Which celestial

intuition would have caused him to draw exactly

this bicycle with the meticulous detail of chain

and chainwheel that was already drawn by

Leonardo at a time unknown to him? There is no

logical answer to these questions, but the fact

that a young man drew a bicycle in the middle of

the 16th century appears to be quite unimportant

to Pedretti. He pleads to pass this problem

over, as if it would suffice to close one’s eyes

to let the bicycle disappear. I don’t believe

that other scholars are ready to follow this

willful proposal.”

Whereas Marinoni’s recent Internet Web page of

the city of Legnano[23]

contends, “This is a decisive argument on which

I could not rely in 1972.”

Evidence

In 1961 the translucent back side showed

geometrical circles and lines. The bicycle

sketch definitely was not there, since its thick

brown crayon would have been detected easily in

translucence.[24]

The forger(s) made economic use of the lines

already present (to minimize crude erasures like

the ones between the wheels) which explains the

idiosyncrasies of the handlebar design.

Accordingly, the bicycle sketch is definitely a

recent forgery that can be dated between 1967

and 1974.

To protect the inference that the appearance of

the chainwheel from Codices Madrid within

the sketch of the Codex Atlanticus

warrants the mental authorship by Leonardo

himself, Marinoni leaves the path of truth in

his brochure, stating in the caption to the page

from Codices Madrid (see Fig. 3 center)

and again on his Web page (Ref. 23):

The importance of this coincidence should not be

underestimated, since this is a detail that no

modern forger could know before publication of

the said Codex in the year 1974.

This refers to the facsimile edition of

Codices Madrid, Ref. 13. But—see above—there

were numerous newspapers and news magazines

worldwide reporting this very sample page in

1967, including an Italian publication by Nando

di Toni in 1967.[25]

It can be predicted that Marinoni or his

Internet-publishing entourage will use his

piecemeal release of discovery detail to claim

now that he discovered the sketch before 1967;

but having lied once, he will no longer be

believed by academia.

Jingoism Forever

In 1983, three American authors realised

that a nonsteerable two-wheeler was no longer

credible and assembled a steerable one from

Leonardo’s machine elements. Their paper was

apparently rejected by American referees of

history of technology (assembling a dishwasher

from Leonardo’s elements does not prove he

thought of one), but not by the German journal

Technikgeschichte.[26]

Their article disclosed the following:

“Dr. Silvio A. Bedini of the Smithsonian

Institution informed us amiably that Dr. Reti

has still been convinced until his death that

the drawing is not genuine and therefore he

would not include it in his volume [The

Unknown Leonardo, Ref. 4]. Professor

Marinoni took over the editorship after Reti and

decided to include the sketch.”

Thus we now have another reason for the delayed

disclosure—Reti’s opposition until his death in

1974. When Marinoni was invited to give a

presentation at the 2nd Cycling History

Conference in St. Etienne in 1991,[27]

he was confronted by the author of this paper

with this statement of the leading Leonardo

expert with a technological background. In

return, Marinoni presented as a humorous

anecdote that Reti indicted him to be the

forger, which was unfortunately not recorded in

the Proceedings, but can now be found on

the Web page Ref. 23:

“The first opponent was Ladislao Reti, whom I

told the discovery during my first examination

of the restored codex, while I wrote a report

for the Commissione Vinciana in Rome. Reti

denied resolutely any possibility that Leonardo

could imagine such a vehicle in the 15th

century. But when I accompanied him into the

Biblioteca Ambrosiana and he was before the

picture he had to admit: ‘This is really a

bicycle—therefore it is a forgery.’ ‘Who has

done it? And when?’ I asked him. The answer was

more extraordinary still than the discovery:

‘This was done by you!’ [L’hai fatto tu!]”

Again, Marinoni fails to date this incident.

So what was the motive of the forger(s) or the

uninitiated discoverer and maintainer with a bad

scholarly conscience? Perhaps the following

passage, written in 1949 by the Italian literate

Curzio Malaparte gives us the answer:

“In Italy, the bicycle belongs to the national

art heritage in the same way as Mona Lisa by

Leonardo, the dome of St. Peter or the Divine

Comedy. It is surprising that it has not

been invented by Botticelli, Michelangelo, or

Raffael. Should it happen to you, that you voice

in Italy that the bicycle was not invented by an

Italian you will see: All miens turn sullen, a

veil of grief lies down onto the faces. Oh, when

you say in Italy, when you say loudly and

distinctly in a café or on the street that the

bicycle—like the horse, the dog, the eagle, the

flowers, the trees, the clouds—has not been

invented by an Italian (for it were the Italians

that invented the horse, the dog, the eagle, the

flowers, the trees, the clouds) then a long

shudder will run down the peninsula’s spine,

from the Alps to the Eatna.”[28]

Fig.

1 (L), 3 (R) Fig.

1 (L), 3 (R) |

|

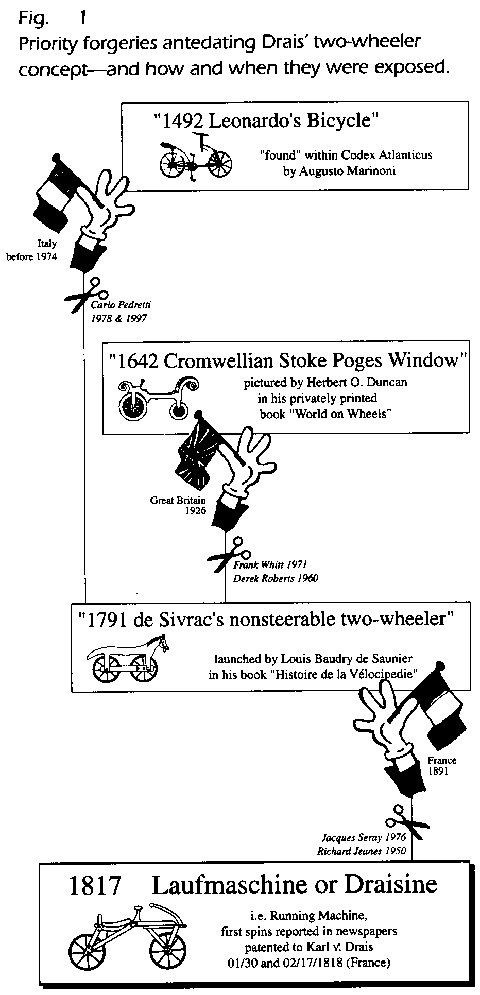

Fig.

2 of original article Fig.

2 of original article |

Fig.

4 of original article, also Fig "Update-1" Fig.

4 of original article, also Fig "Update-1"

|

fig.

" fig.

" |

|

Footnotes / Bibliography

1. Keizo Kobayashi. Histoire du

Vélocipède de Drais à Michaux 1817-1870 –

Mythes et Réalités. Bicycle Culture

Center, Tokyo, 1993.

2. Jacques Seray, in: Cyclisme

(Paris), No. 100, April 1976), pp. 17-21;

Jacques Seray. Deux Roues – La véritable

Histoire du Vélo. Editions du Rouergue,

1988.

2a. Robert W. Jeanes. Des origines du

vocabulaire cycliste français.

unpublished thesis, Université de Paris,

1950.

3. Herbert Osbaldeston Duncan. The World

on Wheels, Paris, 1926, p.265. In

reality, the Stoke Poges window shows a

one-wheeled waywiser for land surveyors; see

Frank R. Whitt in Cycletouring

(London), 10.6.1980 and Derek Roberts in

The Boneshaker, No. 20 (1860).

4. Ladislao Reti (ed.): The Unknown

Leonardo, 3 volumes. McGraw-Hill, New

York, 1974 (the Italian original appeared

under the title Leonardo, 1974 in

Milan; versions in other languages by

national publishers), Vol. 2, Appendix “The

Bicycle” by Augusto Marinoni.

5. Derek Roberts. Cycling History – Myths

and Queries. John Pinkerton, Birmingham,

1991, pp. 17–19.

6. Arturo Uccelli. Storia della Tecnica

dal Medio Evo ai nostri Giorni. Hoepli,

Milan, 1944, p. 627–632.

7. Nando de Toni. L’iniziativa che ha

portato al restauro di codice atlantico.

Notiziario Vinciano (Brescia), No. 1 (1982),

pp. 11–38.

8. Enrico Galbiati, letter of 17.10.1987 to

Keizo Kobayashi, see Ref. 1, p. 344.

9. e.g. Newsweek (New York),

27.2.1967, p. 43, sporting the caption

“Leonardo’s bicycle-like drives,” to the

wrong figure; Der Spiegel (Hamburg),

No. 11/1967 p. 137, “mit der Vorrichtung zur

Kraftübertragung nach Art der Fahrradkette;”

Epoca (Milan), 12.3.1967, p. 83,

“schizzi di transmissioni a cateno sul tipo

di quelle adottate per le biciclette.”

10. Ladislao Reti, “The two unpublished

Manuscripts of Leonardo da Vinci in the

Biblioteca Nacional of Madrid” I,

Burlington Magazine, No. 778, vol. 110

(Jan. 1968), p. 18.

11. Codex Atlanticus fol. 158r

12. Paolo Galuzzi. Renaissance Engineers

–From Brunelleschi to Leonardo da Vinci.

Exhibition catalog, Giunti, Florence, 1996,

p.222.

13. Leonardo da Vinci: I Codici di Madrid.

Introduction by L.Reti, glossary and index

by A. Marinoni. Giunti, Florence, 1974

(versions in other languages by national

publishers).

14. A. Marinoni, “I codici di Madrid,” XIV

Lettura Vinciana, Giunti BarbÅra, Florence

1974 (lecture given on 20.4.1974 in the

Biblioteca Leonardiana in Vinci).

15. Il Codice Atlantico di Leonardo da

Vinci. Transcribed by Augusto Marinoni,

Giunti edi tion. Florence 1973–1975. 25"

high, 998 copies printed.

16. Il Codice Atlantico di Leonardo da

Vinci,.Hoepli, Milan, 1894–1904, 21"

high, 280 copies printed.

17. Augusto Marinoni, “Una bicicletta come

nuova.” L’Espresso (Milan), No.16,

21.4.1974, pp. 98-99.

18. Nando di Toni, Letteri ai Direttore,

L’Espresso (Milan), No.20, 19.5.1974, p.

187.

19. Augusto Marinoni, “Leonardo da Vinci:

l’automobile et la bicicletta.” Arcadia

(Milan), 1981 (expanded version of a former

lecture:). Augusto Marinoni, “L’automobile

et la bicicletta di Leonardo,” in: Atti

della Societe Leonardo da Vinci

(Florence) a.73, vol. 6 (1975), pp. 285–292.

20. Giovanni Maria Pace, “Che et ha la bici.”

Panorama (Milan), 9. May 1974, p.

109.

21. Carlo Pedretti. The Codex Atlanticus

of Leonardo da Vinci: A Catalogue of its

newly restored Sheets. Part One and Two.

Harcourt-Brace-Jovanovich, New York, 1978

(descriptions only, no facsimiles).

22. Carlo Pedretti, personal communication,

1997; a more exact tracing was lost in Los

Angeles due to a car theft in 1965, see:

Carlo Pedretti. Leonardo da Vinci – The

Royal Palace at Romorantin. Harvard

University Press, Cambridge, 1972, p. 142.

23. “Uno studio del prof. Augusto Marinoni

sulla bicicletta e l’automobile di Leonardo”

Edizione 1996 (Febr. 1996) http://www.nemo.it/leon/bicinew.htm.

24. Carlo Pedretti, personal communication

to the author in 1997.

25. Nando de Toni, “Contributo alla

conoscenza dei manoscritti Vinciani 8936 e

8937 della Biblioteca Nazionale di Madrid,”

Physis (Italy), anno 9 (1967) fig.

11a.

26. Vernard Foley, Edward R. Blessman, James

D. Bryant, “Leonardo da Vinci und das

Fahrrad,” Technikgeschichte, 50

(1983), Nr. 2, p. 103.

27. Augusto Marinoni, “Leonardo da Vinci’s

Bicycle,” in: Actes de la Deuxième

Conférence Internationale sur l’Histoire du

Cycle, St. Etienne 1991. Quorum,

Cheltenham, UK, 1992.

28. Curzio Malaparte, “Les deux visages de

l’Italie: Coppi et Bartali,” in: Sport

Digest (Paris) No. 6, 1949, pp. 105–109.

|

|

Updates and Additional

Information

Article published in The Boneshaker,

the journal of the Veteran Cycling Club

From issue No. 147, also by Hans-Erhard

Lessing:

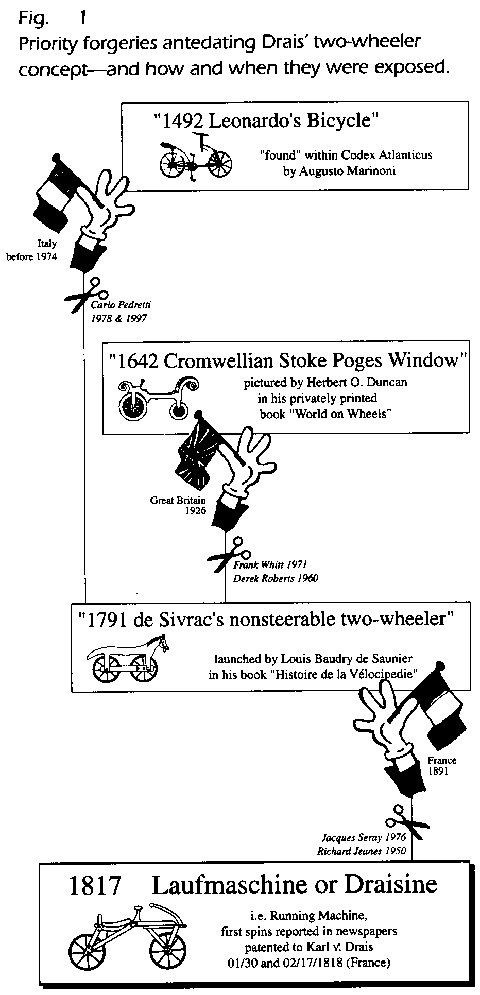

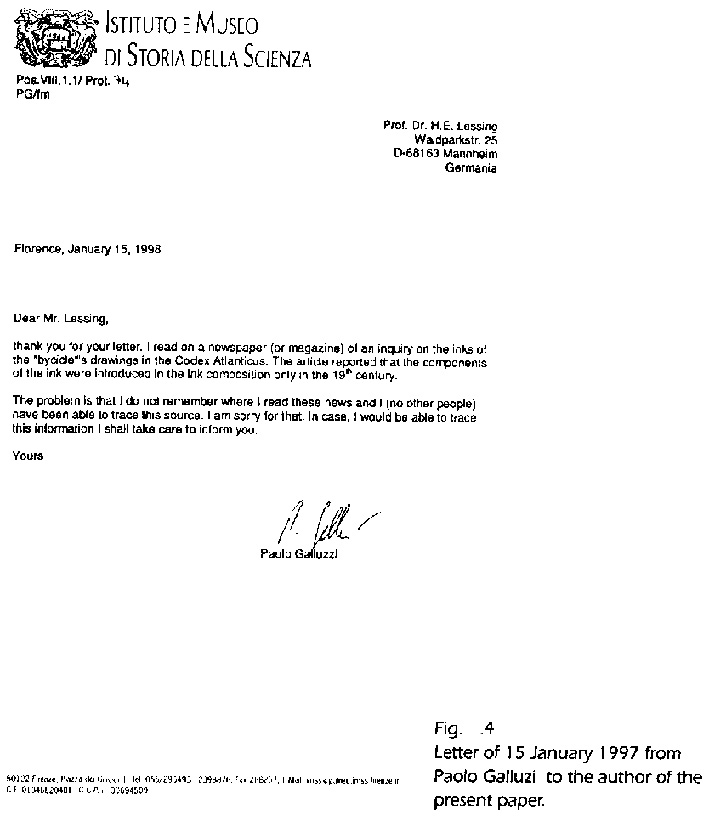

Disclosure of the revelation of the

Leonardo-bicycle forgery by the New

Scientist[1] resulted in considerable

press and radio coverage throughout Europe

and Canada. Subsequent research by the

French journalist Serge Lathière for an

article [2] brought news of an age test on

the bicycle scribble, best described by

himself in a fax to Monsignore Prof

Gianfranco Rabasi, the director of the

Biblioteca Ambrosiana, where the Codex

Atlanticus is kept:

“…I have just finished to write a paper

about the ‘Leonardo da Vinci bicycle.’ But

I've learned this morning that the page

where the bicycle was drawn was recently

dated. So I'm sending you this fax to get

more information. Which team made the

datation? What was dated (the ink used to

draw the bicycle?) What kind of technique

was used? What were the results? From Carlo

Pedretti and Paolo Galluzzi I've learned

they found two kinds of ink:one made after

1880 and another made after 1920. In this

case the bicycle would be a fake. Could you

confirm this information as soon as

possible, because my article has to be sent

for printing very soon now…”

In fact, Pedretti confirmed in a phone call

the same day that he was told all this by

Prof. Paolo Galluzzi, director of the

Science Museum in Florence, who reportedly

had read the news in the airplane but not

noted the source. The test was “nuclear

something,” as Pedretti put it. To the

dismay of Lathière, Ravasi refused to

comment, although his library keeps the

Codex Atlanticus[4]:

“The library does not conduct research nor

give information of the kind that you

request. The library is open Monday through

Friday from 9 till 17:30 o'clock. Cordiali

saluti.”

A recent letter by Galluzzi to the author

confirms in essence what was said above

(see Fig “Update-1”). Hence not even the

two circles are from Leonardo's hand.

As late as the January 1998 issue of

Scientific American, Marinoni's US

partisan, Vernard Foley of Purdue

University, returned with a vastly improved

Leonardo bicycle replica, this time with a

brand new brake operated by a pulling rope

(see Fig. “Upate-2”). It came as an

illustration within an article on Leonardo

and the invention of the wheellock.[5].

Rectifying letters to the editor of

Scientific American by David Gordon

Wilson from MIT and me were not printed in

subsequent issues. Remember, Foley had

built the steerable Leonardo bicycle from

Leonardo's machine elements in 1983[6].

Instead of a response to the recent letter

to the Editor of the Boneshaker, I

shall reprint Marinoni's view of the 2nd

International Cycling History Conference in

St. Etienne, 1991, where he was invited to

speak. The text stems from Marinoni's

website[7] and for the sake of brevity, only

the relevant section is presented here in an

English translation:

“astonished the experts and there were

spontaneous but unspecific challenges to its

authenticity. However the vigorous

skepticism of critics has failed to

undermine any of (the) evidence for

authenticity set up by Professor Augosto

Marinoni, the leading Vinci scholar (pag.

12)”

Footnotes to update

1. Jonathan Knight. “On your bike,

Leonardo.” New Scientist, Vol. 156,

No. 2104 (18 October 1997), p. 28.

2. Serge Latière. “Léonard da Vinci a perdu

son vélo.” Science et Vie Junior, No.

100 (Jan. 1998), p. 24.

3. Communicated to the author the same day,

25 November 1997.

4. Fax of 27 November 1997 to Lathière,

communiated by letter to the author.

5. Vernard Foley. “Leonardo and the

Invention of the Wheellock.” Scientific

American, 278 (January 1998), pp. 74-78.

6. Vernard Foley, Edward R. Blessman, James

D. Bryant. “Leonardo da Vinci und das

Fahrrad.” Technikgeschicte, 50

(1983), No. 2, pp. 100-128.

7. Now at http://rcl.nemo.it/retecif/cultura/arte/leon/bicispag1.htm

(Febbraio 1996).

8. Roland Sauvaget with his brilliant French

summary of all objections.

|

|

Fig.

1 (L), 3 (R)

Fig.

1 (L), 3 (R)

Fig.

2 of original article

Fig.

2 of original article  Fig.

4 of original article, also Fig "Update-1"

Fig.

4 of original article, also Fig "Update-1"